Delve into India’s rich jazz history, tracing its arrival in the 1930s and the influential figures like Teddy Weatherford and Chic Chocolate who shaped its sound. The article examines jazz’s significant role in Hindi film music and early Indo-jazz fusion, showcasing India’s distinct contribution to the global genre. It reveals Bombay as a key cosmopolitan center for this musical evolution.

Jazz, a vibrant musical form born in the melting-pot town of New Orleans in the early years of the 20th century, quickly transcended its American origins to become a global phenomenon. By the 1950s, this fusion of syncopated African rhythms, bluesy melodies, lush European harmonies, and Iberian influences would surprisingly become a significant ingredient in Hindi film music, putting a distinct “spring in India’s step”. Mumbai, then Bombay, emerged as a pulsating center for this new musical genre, fostering a rich and complex history of cultural exchange and artistic innovation that preceded similar Western efforts by two decades. The period from the 1930s to the 1950s is often referred to as the golden age of jazz in India.

The Grand Arrival: African American Pioneers and the Bombay Scene

The groundwork for jazz’s flourishing in India was laid in the 19th century by various forms of American popular culture, including minstrelsy shows by troupes like Dave Carson’s from the 1860s. However, the true jazz era began in earnest with the arrival of African American musicians. The earliest traveling groups to India in the mid-1930s were led by Herb Flemming and Leon Abbey.

In 1935, Bombay’s premier hotel, the Taj Mahal, made a landmark decision by hiring the first all-African-American jazz band to play in India. This eight-member ensemble was led by Leon Abbey, a violinist from Minnesota. His band was staffed by experienced musicians who had performed alongside legends. Among them were:

- Emile Christian: Trombone and bass player, a member of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band.

- Ollie Tines: Drummer, who had toured Scandinavia with Louis Armstrong.

- Charles “Dizzy” Lewis: Pianist, who had played at Chez Florence in Paris.

- Crickett Smith: Trumpeter, featured on seminal recordings that captured the transformation of ragtime into sophisticated jazz, and had spent years in Europe helping the French develop their jazz scene.

- Rudy Jackson: Saxophonist, who had performed with King Oliver and briefly with Duke Ellington.

- Fletcher Allen and Arthur “Horse” Lanier: Other saxophonists.

- Castor McCord: Saxophone player who had backed both Louis Armstrong and Coleman Hawkins.

Audience reception to Abbey’s band was initially mixed. The Chicago Defender reported that his style “sent Bombay audiences into a debate that lasted for weeks,” with conservatives demanding “old numbers and old ways”. However, the band adjusted, slowing their “Paris speed” to “Bombay speed,” and eventually gained “wholehearted approval,” with the Defender proclaiming Abbey had “Introduces Swing Music in India”.

Bombay itself was a city on the rise in the 1930s. Recovering from the global economic depression, its population boomed, attracting new residents to industrial plants and expanding cotton textile mills. The city embraced the streamlined Jazz Age style of art deco, visible in new cinema halls and buildings along reclaimed land. The advent of sound in films in 1931 also solidified Bombay’s position as the movie capital of India, drawing actors, musicians, and writers. This vibrant atmosphere created fertile ground for jazz. The ballrooms of five-star hotels and nightclubs became jazz centers, attracting European and Indian elites.

Other notable early African American musicians included Crickett Smith, who led a band at Bombay’s Taj Mahal Hotel that featured several Indian musicians. Teddy Weatherford eventually settled in India, forming a crucial “bridge between the African-American musicians and the Indian musicians”. Weatherford, a “formidable pianist” who had played with Louis Armstrong in Chicago in the 1920s, arrived in India in 1936 and was hailed as “The Real Thing”.

The Rise of Indian Jazz Talent

Inspired by these visiting maestros, a generation of Indian musicians stepped onto the jazz scene:

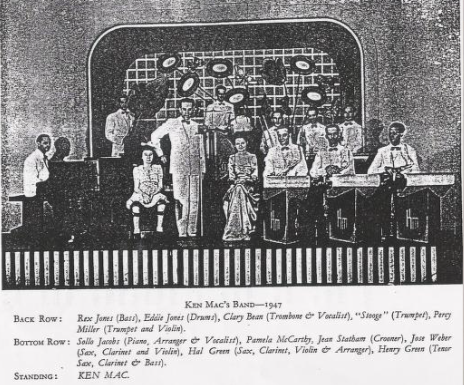

- Ken Mac: An Anglo-Indian, styled himself as the “pioneer of dance bands in India”. He started playing drums in 1922 and rose to fame as a bandleader, making over two dozen discs showcasing his “elegant dance music with a touch of swing”. Mac’s bands often played at “whites-only establishments” like the Bombay Gymkhana and Royal Bombay Yacht Club, and he was known to hide darker-skinned Goan musicians in the back rows.

- Henry and Hal Green: Anglo-Indian brothers who formed the eight-member band Elite Aces in Bangalore in 1933, performing “dance music with a jazz accent”. Hal Green was a multi-instrumentalist (guitar, reeds, violin) and arranger, while Henry played bass and saxophone.

- Josic Menzie: A multi-instrumentalist from the Seychelles, trained in England, who joined the band at the Taj, playing alongside Weatherford and the Green brothers. In his later years, he became a revered teacher, helping young Mumbai musicians discover a passion for jazz and Western classical music.

- Rudy Cotton (Cawasji Khatau): A Parsi saxophonist, a rarity in the jazz scene dominated by Anglo-Indians and Goans. He was an avid student of jazz, famously hanging around the Taj to chat with members of Leon Abbey’s band. By 1940, he formed his own all-Indian band, which “really jumped”.

- Goan Musicians: Many musicians were Goans, who had learned Western music under Portuguese rule. This training proved invaluable, as their ability to read staff notation set them apart from Hindustani-trained musicians. They quickly established themselves as the “musicians of the Raj,” staffing orchestras and later, accompanying silent films.

Jazz Finds its Voice in Bollywood and Beyond

The 1940s marked a crucial turning point as jazz began its indelible integration into Hindi film music. Goan musicians, with their unique Western music training, found themselves at the heart of this creative explosion, often acting as assistant music directors.

- Chic Chocolate (Antonio Xavier Vaz): Known as the “Louis Armstrong of India,” he made his mark through his trumpet solos in films like Samadhi (1950) and his appearance in Albela (1951), where his band featured in costumes. Chocolate’s music, infused with Latin American rhythms and his signature trumpet licks, “enlivened” countless Hindi film soundtracks, forming the basis of set-piece songs and incidental music. He later became a music director for Nadaan.

- Frank Fernand: A trumpet player whose “epiphanic encounter with Mahatma Gandhi” in 1946 inspired him to seek a uniquely Indian expression for jazz. Fernand became a prominent figure in the Hindi film industry, working as an arranger and assistant music director for composers like Roshan and Anil Biswas. His original composition “Prabhat” (“dawn”), an “Indian theme,” was a highlight of a 1948 All Star Band concert in Bombay.

- Anthony Gonsalves: A violinist and film arranger, whose passion leaned towards Western classical music. He meticulously worked to meld Indian classical music with Western systems, composing pieces like “Concerto in Raag Sarang”. His name achieved widespread fame in 1977 due to the Bollywood film Amar Akbar Anthony, where a character was named after him.

The Bombay Swing Club, formed in November 1948 by Hal and Henry Green and Frank Fernand, aimed to promote live jazz performances after initially being a record listening club. Its inaugural concert faced a severe cyclone, yet was a “grand success”. The club hosted performances by its “Ork” at venues like the Taj Mahal Hotel, Sundarbai Hall, St Xavier’s College, Eros Theatre, and the Central YMCA, which also provided rehearsal space. The club welcomed a diverse audience, from “surgeons, typists, mill owners, railwaymen, socialites, journalists, clerks, musicians and stenographers”. They featured original compositions by prominent local musicians such as Chic Chocolate’s Naga Serenade, Frank Fernand’s Swing Finale and Oriental Fantasy in Swing, Hal Green’s Lapis Lazuli and Woodwind Rhapsody, and Johnny Gomes’s Carinesque and Quince Jam Jump. The club also sought to get these Indian compositions published abroad, lamenting the lack of local facilities.

Other significant figures of this era included:

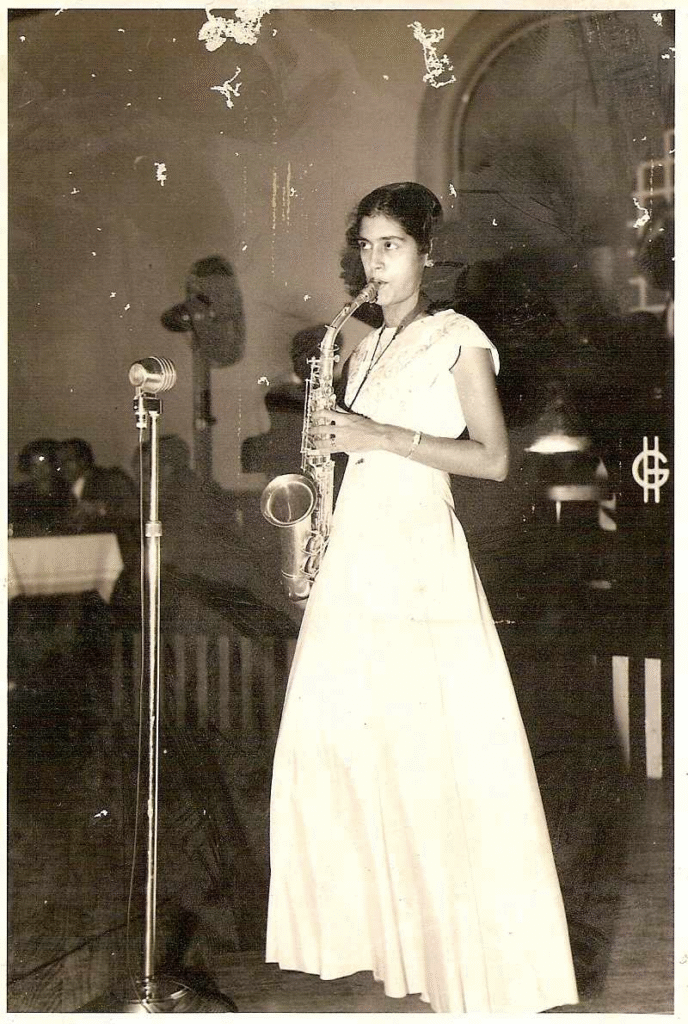

- Lucilla Pacheco: One of the few female instrumentalists on the Bombay jazz scene in the 1940s, she played in Micky Correa’s all-star band at the Taj Mahal Hotel and with Ken Mac. She later joined the Hindi film industry.

- Johnny Baptist: His “first big break was in 1940” with Rudy Cotton’s band at the Taj. Proficient on violin, clarinet, and saxophone, he formed his own band in 1948.

- Paquita and Zarate: A duo prominent in 1940s Calcutta for their jazz and swing recordings of Hollywood tunes.

- “Jazzy” Joe Pereira: Started performing in 1941 at age 14, playing saxophone in clubs across Lahore, Calcutta, and Bombay.

- Ken Cummins: Known as Bombay’s “hottest jazz violinist”.

The Evolution of Indo-Jazz and International Encounters

The post-independence era saw a deeper engagement with jazz. Recognizing similarities between jazz and Indian classical music, especially improvisation, collaborations began to flourish, leading to the development of Indo-jazz. Figures like Ravi Shankar, John Coltrane, John Mayer, and John McLaughlin were pioneers of this fusion, with Indian classical music even influencing the jazz subgenre of free jazz.

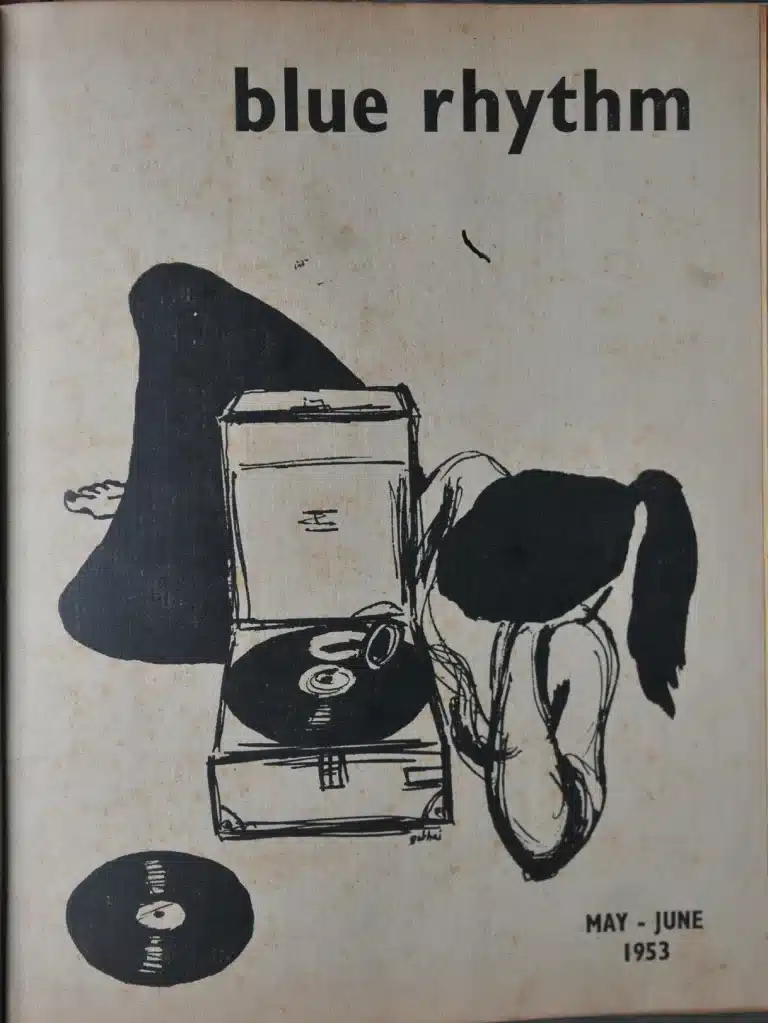

The “Austin High” group of young jazz enthusiasts in Bombay, including Niranjan Jhaveri, Jehangir Dalai, Coover Gazdar, Yusuf Curmally, and Soli Sorabjee, played a crucial role. As schoolboys, they developed their passion listening to jazz programs on Radio SEAC. In 1952, they launched Blue Rhythm, India’s first jazz magazine. Despite a short run (until September 1953) due to financial and time constraints, the magazine’s seven issues offered a vivid snapshot of the evolving Indian jazz scene. It featured debates between Dixieland (“mouldy figs”) and bebop (“sour grapes”) fans, although it initially lacked coverage of local musicians. Blue Rhythm also faced challenges with import barriers for records but provided readers with information on how to obtain foreign recordings and promoted jazz via radio programs. The magazine’s successful concerts, featuring musicians like Rudy Cotton and the British Modern Jazz quintet, helped consolidate jazz’s place in India and later paved the way for the Jazz Yatra festival.

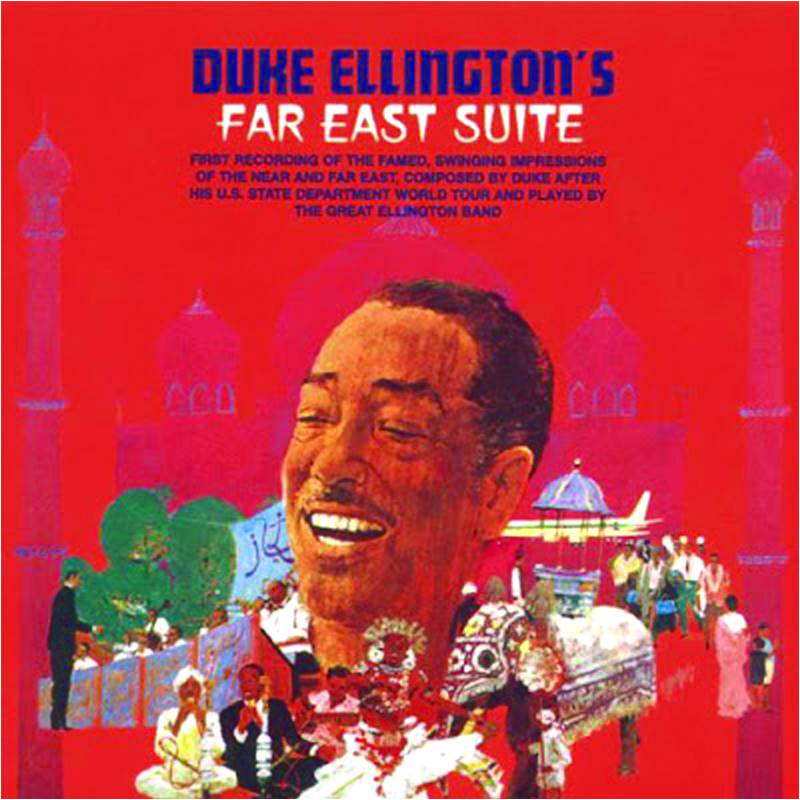

The Cold War era also brought a new dimension to jazz in India, as the US State Department used jazz as a “Cold War weapon”. Tours by renowned American jazz artists like Dave Brubeck (1958), Dizzy Gillespie (1956), Jack Teagarden (1959), Duke Ellington (1963), and Louis Armstrong (1964) were designed to promote American culture, showcase racial harmony, and counter communism.

These tours often included jam sessions and discussions with Indian musicians, although cultural misunderstandings (like Duke Ellington’s experience with headshakes meaning “yes” for food) sometimes arose.

Several Indian musicians gained prominence during this period, often interacting with their American counterparts:

- Dizzy Sal (Edward Saldanha): A talented pianist from Rangoon, he so impressed Dave Brubeck during his 1958 tour that Brubeck secured him a scholarship to study at the Berklee College of Music in Boston in 1959. Sal became the first Indian to play jazz at important venues in the US and even cut a well-regarded record. Despite his initial success, his dreams “began to darken” after returning to India, and he rarely performed publicly due to illness.

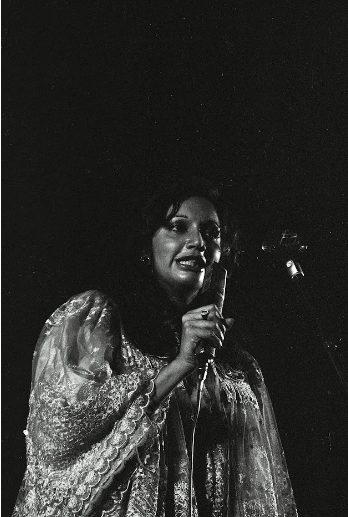

- Pam Crain: Known as the “Empress of Park Street,” she began recording in 1954 and became one of India’s most expressive jazz vocalists.

- Braz Gonsalves: A saxophonist who “shot to fame” at the Venice restaurant in the Astoria Hotel in the 1960s. He played both alto and soprano sax and was considered “the most sophisticated jazz musician India had ever produced” at the time. He was a pioneer of Indian-influenced jazz, experimenting with improvising on ragas.

- Asha Puthli: Renowned for her “sultry vocals” on Ornette Coleman’s Science Fiction album, for which she won the prestigious ‘Downbeat critics poll award’ alongside Ella Fitzgerald. She was trained in Hindustani classical vocals and opera and learned jazz by listening to the Voice of America on the radio.

- Louis Banks: Born to jazz trumpet player George Banks (named after Louis Armstrong), Louis Banks became India’s best-known jazz keyboardist. He led bands in Calcutta and later performed in fusion projects, including with Carnatic vocalist Rama Mani and Braz Gonsalves.

- Toni Pinto: A “noted technical virtuoso” pianist who led the band at the Ambassador Hotel in Bombay for many years. He also composed original tunes like “Forever True”.

By the end of the 1950s, the Bombay jazz scene was changing. Foreign musicians were scarce due to currency restrictions, and many first-generation Indian jazz musicians, like Frank Fernand, retreated into the lucrative film studios. A younger generation of musicians emerged, favoring bebop and the “cool style” over older Dixieland and swing classics, and new venues focused on listening rather than just dancing.

Legacy and Beyond

Despite the challenges, the influence of jazz persisted. While the Churchgate Street strip, once vibrant with jazz clubs like Volga, Bistro, and The Other Room, eventually fell silent due to new taxes, Bollywood continued to offer a refuge for many jazzmen. The large orchestras of film composers provided steady work, even if the musicians sometimes “didn’t enjoy the kind of music they were playing” as much as jazz.

Chic Chocolate passed away in May 1967 at the age of 51, his casket carried by prominent Bombay musicians. His legacy, like that of many other pioneers, lives on in the melodies that defined an era.

The history of jazz in India is one of dynamic cultural exchange, adaptability, and innovation. Indian musicians not only absorbed but also enriched jazz, leading to unique fusions that preceded global trends. While the widespread popularity of jazz as a “world’s pop” has waned, giving way to rock and roll and later techno and hip hop in Bollywood, it remains a “pedigreed minority art”.

Jazz profoundly shaped the cultural and social fabric of Mumbai (then Bombay) from its arrival in the mid-1930s, becoming far more than just a musical genre.

Of the many way ways jazz influenced the sleepless city:

- A Catalyst for Cosmopolitanism and Social Interaction: Jazz venues, particularly the grand ballrooms of five-star hotels like the Taj Mahal, Green’s Hotel, and later clubs, became crucial social centers and melting pots. They brought together diverse communities, including foreign African-American and European musicians, Goans, Anglo-Indians, Parsis, and other Indian elites and public servants. This fostered a “conspicuous cosmopolitanism” in the city. The Bombay Swing Club, for instance, welcomed “all music-lovers,” from surgeons and typists to mill owners and socialites, highlighting jazz’s broad appeal across class lines.

- Shifting Social Norms and Public Life: Jazz, through its associated Western dance forms (like the foxtrot and rumba), challenged existing social conventions, particularly regarding gender mixing and public display. While older generations found it “unseemly”, the younger set enthusiastically embraced dancing. The music initially served as entertainment for the European and Indian elite, aristocrats, and the wealthy. However, it gradually made its way to the working class and into Hindi films, democratizing its reach. The emergence of jazz was also linked to Bombay’s rapid modernization and economic recovery in the 1930s, with its “frenetic rhythms” reflecting the “hyperkinetic tempo of modernity”.

- Profound Influence on Hindi Film Music (Bollywood): Jazz became an “important ingredient in Hindi film music,” injecting a new energy into Indian cinema’s soundtrack. This was partly due to Goan musicians, who, trained in Western music under Portuguese rule, possessed the unique technical skills (e.g., reading staff notation, understanding Western harmony) to integrate jazz and swing into film scores. Pioneers like Chic Chocolate and Frank Fernand (often credited as assistant music directors) were instrumental in arranging music for Bollywood orchestras, introducing elements like Dixieland stomps, Ellingtonesque doodles, and Latin American rhythms (rumba-samba) into film songs. Songs like “Deewana Parwana” from Albela (1951) and “Gore Gore” from Samadhi showcased this integration. Jazz in films also came to symbolize “bold modernity”, often accompanying plotlines about young love challenging traditional arranged marriages.

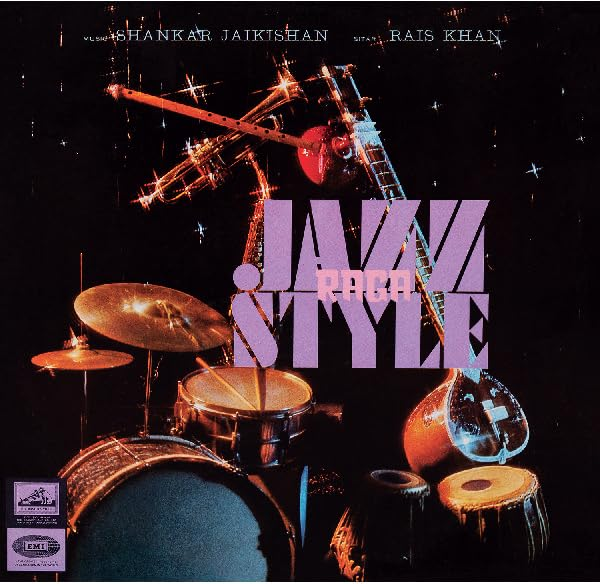

- Experiments in Indo-Jazz Fusion: Indian musicians actively explored ways to fuse Hindustani classical music with jazz, with their initial experiments predating similar Western efforts by two decades. Frank Fernand, inspired by Mahatma Gandhi, sought to give jazz a “uniquely Indian expression”. Anthony Gonsalves aimed to blend Eastern and Western instruments and styles, scoring Indian ragas for orchestras and choirs, demonstrating that Indian music could offer a “universal form of expression”. Later works like Sebastian D’Souza’s Raga Jazz Style (1968) and collaborations by Braz Gonsalves and Amancio D’Silva continued to push these boundaries, creating “really creative music” that was ahead of its time.

Emergence of a Dedicated Jazz Community and Media:

The city saw the formation of organizations like the Jazz Society (1946) and the Bombay Swing Club (1948), which organized jam sessions, concerts, and record-listening events to promote jazz beyond hotels.

The launch of “Blue Rhythm” magazine in 1952 provided a dedicated platform for jazz fans, featuring profiles of American musicians, record reviews, and local debates on jazz styles (Dixieland vs. Bebop). It also served as a vital source of information amidst import restrictions for records.

Radio broadcasts, particularly Radio SEAC, played a significant role in educating listeners and exposing them to progressive jazz during WWII. The Voice of America’s jazz programs, despite inconvenient timings, also cultivated a love for the genre.

Artistic and Architectural Expression:

Beyond music, jazz became a metaphor for “freedom of expression” and improvisation. The Art Deco architectural style, popular in Bombay during the Jazz Age, drew inspiration from “streamlined Jazz Age” aesthetics, with motifs appearing on new buildings and cinemas like the Regal and Liberty Cinema.

Despite a decline in its regular performance after the 1960s with the rise of pop and rock and roll, the legacy of jazz in Mumbai survived through initiatives like the biennial Jazz Yatra festival, which during its life from 1978 till 2004, was the longest running Jazz festival, outside of Europe, ensuring continued interaction between Indian and international jazz musicians and cementing its place in the city’s cultural history.

Drawing on the information from the sources and our conversation history, here is a reference list for the materials provided to me, followed by a bibliography of key works that underpinned the content, especially those extensively cited within the sources themselves.

Reference List

- American Institute of Indian Studies. “Finding the Groove: Pioneers of Jazz in India 1930s-1960s.” Google Arts & Culture. Based on archival materials collected by Naresh Fernandes at the Archives and Research Center for Ethnomusicology, AIIS, and Taj Mahal Foxtrot by Naresh Fernandes.

- Wikipedia. “Jazz in India.” (Accessed through provided excerpt; specific access date not provided).

- Fernandes, Naresh. “Swinging in Bombay, 1948.” Naresh Fernandes’ blog, 30 April 2022.

- Fernandes, Naresh. Taj Mahal Foxtrot: The Story of Bombay’s Jazz Age. Lustre Press | Roli Books, 2012. ISBN: 978-81-7436-759-4.

- Mitter, Suprita. “When Jazz hit Mumbai.” Mid-day, 20 February 2015.

- Anand, Mulk Raj. Private Life of an Indian Prince. Hutchinson, 1953.

- Blue Rhythm. Edited by Niranjan Jhaveri, August 1952 – September-October 1953.

- Bowles, Chester. Ambassador’s Report. Victor Gollancz, 1954.

- Chari, Madhav. “Jazz Music and India.” Mybangalore.com, 10 August 2009.

- Clayton, Buck and Elliot, Nancy Miller. Buck Clayton’s Jazz World. Continuum Publishing, 1989.

- Coleman, Bill. Trumpet Story. Northeastern University Press, 1991.

- Collet, HJ. “Thirty Years of Jazz in India: Our Top Bands Can Swing it With the Best.” The Illustrated Weekly of India, 22 August 1948.

- Davenport, Lisa E. Jazz Diplomacy: Promoting America in the Cold War Era. University of Mississippi Press, 2009.

- Darke, Peter and Gulliver Ralph. “Teddy Weatherford.” Storyville 65, 1976. Also, “Roy Butler’s Story.” Storyville 71, 1977.

- Dwivedi, Sharada and Mehrotra, Rahul. Bombay: The Cities Within. India Book House, 1995. Also, Bombay Deco. Eminence Designs, 2008.

- Ellington, Edward Kennedy. Music Is My Mistress. Da Capo Press, 1976.

- Ezekiel, Nissim. Collected Poems: 1952-1988. Oxford University Press, 1989.

- Gandhi, Mohandas Karamchand. An Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments with Truth. Navjivan Trust, 1927.

- Hawes, Hampton, and Asher, Don. Raise Up Off Me: A Portrait of Hampton Hawes. Thunder’s Mouth Press, 2001.

- Hughes, Langston. I Wonder as I Wander. Hill and Wang, 1993.

- Jackson, Jeffery H. Making Jazz French: Music and Modern Life in Interwar Paris. Duke University Press, 2003.

- Kaminsky, Max. My Life in Jazz. Harper & Row, 1963.

- Karaka, DF. Betrayal in India. Victor Gollancz, 1950. Also, Nehru: The Lotus Eater from Kashmir. Derek Verschoyle, 1953. And There Lay the City. Thacker and Co, 1944. (And other works listed in source).

- Paranjoti, Victor. On This and That. Thacker and Co, 1958.

- Rajabally, AH. “But the Melody Lingers On, Debonair.” September 1972. Also, Those Enchanted Evenings. Unpublished.

- Ramani, Navin. Bombay Art Deco Architecture: A Visual Journey 1930-1953. Roli, 2006.

- Ranade, Ashok da. Hindi Film Song: Music Beyond Boundaries. Promilla, 2006.

- Schuller, Gunther. Early Jazz: Its Roots and Musical Development. Oxford University Press, 1968.

- Shankar, Ravi. Raga Mala. Welcome Rain Publishers, 2001.

- Shope, Bradley. American Popular Music in Britain’s Raj. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2016. Also, “They Treat Us White Folks Fine: African American Musicians and the Popular Music Terrain in Late Colonial India.” South Asian Popular Culture Vol 5, Oct 2007.

- Sorabjee, Soli. “High Notes and Blue Notes.” Span, Oct 1985. Also, “Rudy Cotton – A Legendary Musician.” Rudy Cotton Memorial Concert Souvenir, Jazz India Delhi Chapter, 2005.

- The Chicago Defender. Various years, 1932-1945.

- The Times of India. Various years.

- Von Eschen, Penny M. Satchmo Blows Up the World: Jazz Ambassadors Play the Cold War. Harvard University Press, 2004.

- Yudkin, Jeremy. The Lenox School of Jazz: A Vital Chapter in the History of American Music and Race Relations. Farshaw, 2006.